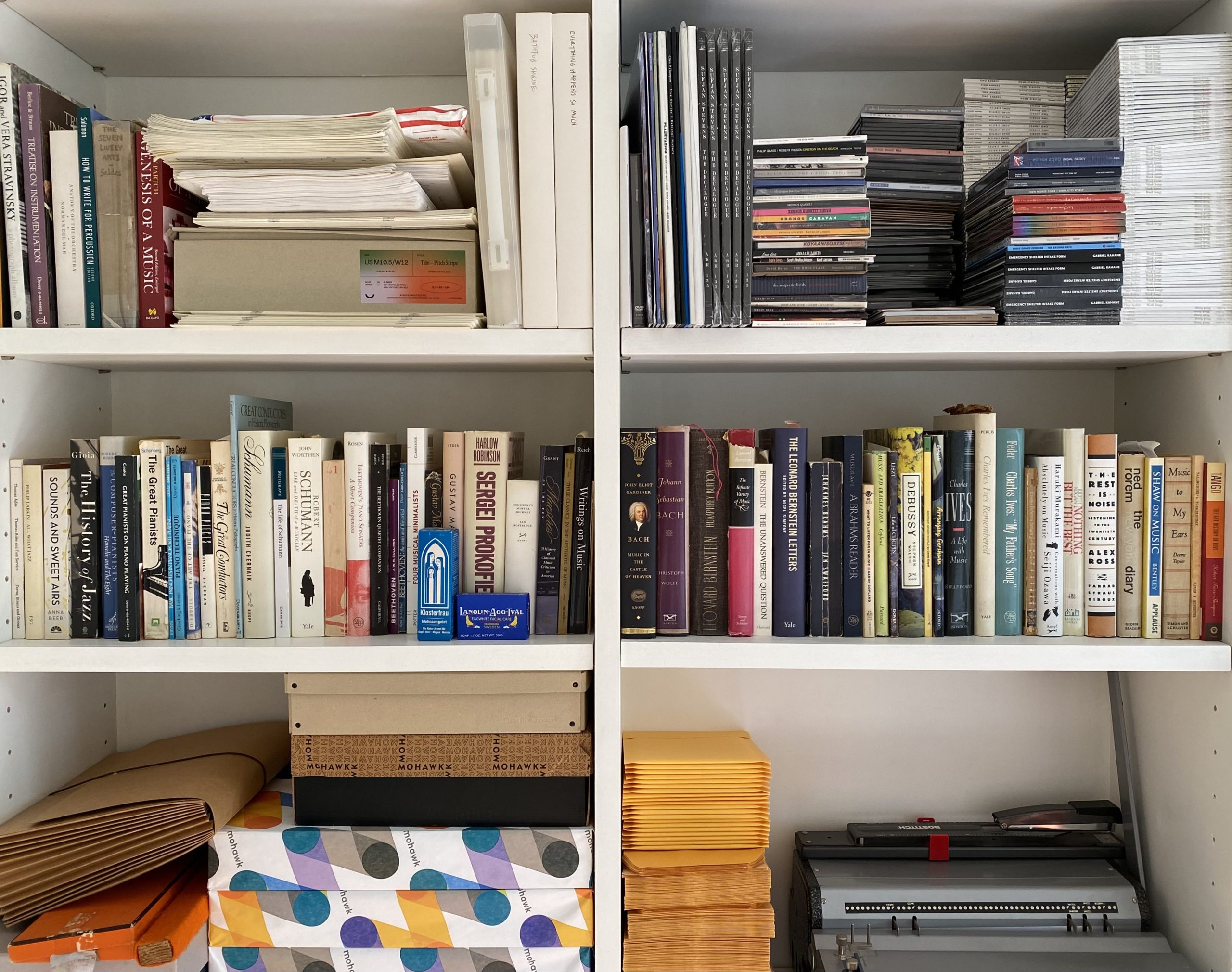

I’m thrilled to reveal that The Blind Banister, a new album that’s been in the works, in some form, for an outrageous nine years, will be released by Nonesuch Records on March 22. You can listen to the last movement of Upstate Obscura, my cello concerto, today. The album was recorded this past summer with cellist Inbal Segev, conductor Andrew Cyr, and Metropolis Ensemble (longtime collaborators who you may remember from Home Stretch).

It’s increasingly rare, impractical, and untenable to record an orchestra in this level of detail, in a studio environment; this may very well be the last album I make in such a way. I am forever grateful to the collaborators who helped bring it into the world: Andrew Cyr and the musicians of Metropolis Ensemble, Inbal Segev, producer Silas Brown, Jonathan Biss (who commissioned and premiered The Blind Banister), Russell Hirshfield (who commissioned and premiered Colorful History), Bob Hurwitz and the team at Nonesuch Records, David Kaplan for a lyrical liner note, Jason Fulford for his enigmatic cover photo, and Ben Tousley for his elegant typography.